Burgers equation on a sequence of meshes¶

This demo shows how to solve the Firedrake Burgers equation demo on a sequence of meshes using Goalie. The PDE

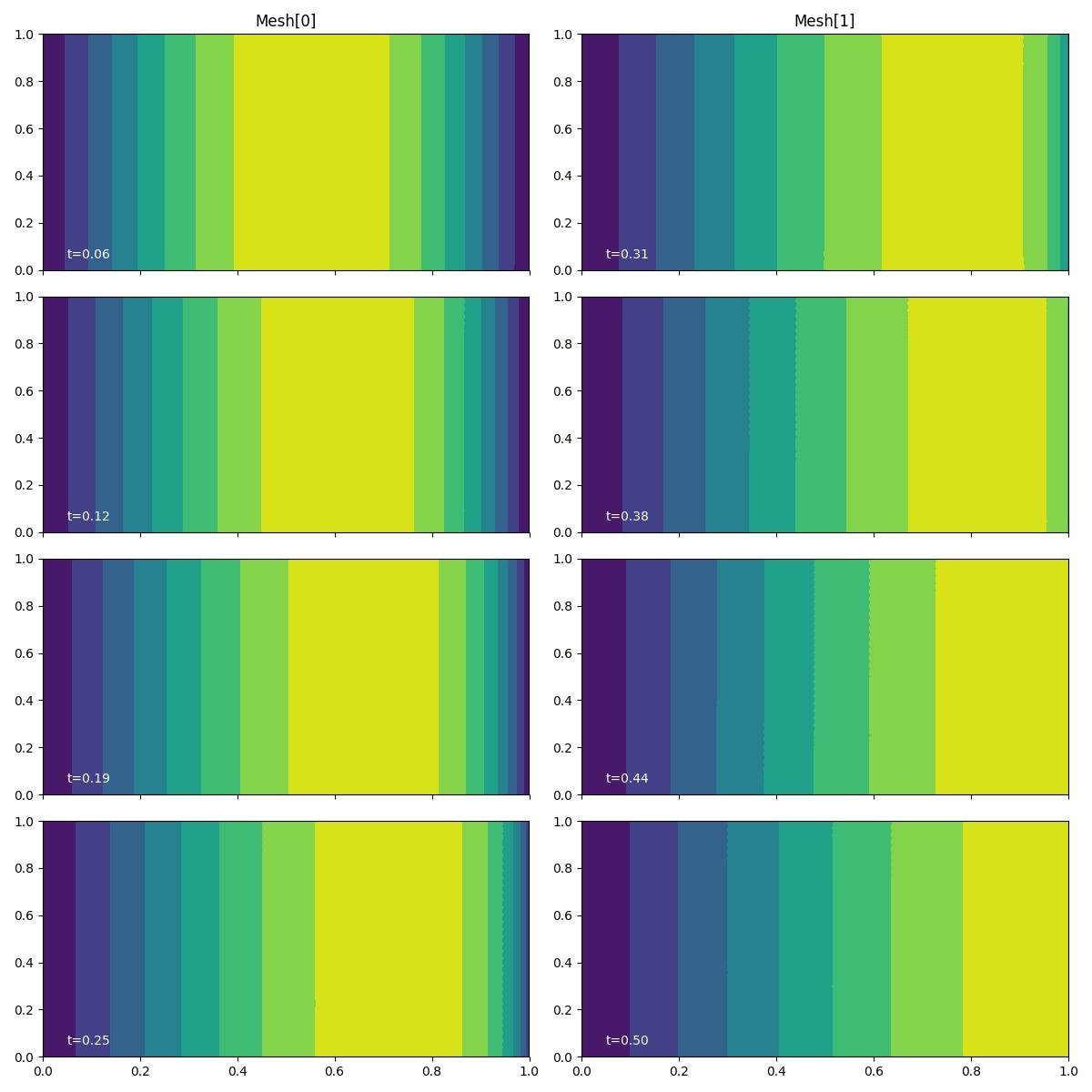

is solved on two meshes of the unit square, \(\Omega = [0, 1]^2\). The forward solution is initialised as a sine wave and is nonlinearly advected to the right hand side. See the Firedrake demo for details on the discretisation used.

from firedrake import *

from goalie import *

We begin by defining the two meshes of the unit sequare that we’d like to solve over. For simplicity, we just use the same mesh twice: a \(32\times32\) grid of the unit square, with each grid-box divided into right-angled triangles.

n = 32

mesh = UnitSquareMesh(n, n)

In the Burgers problem, we have a single prognostic variable, \(\mathbf u\). Its

name and other metadata are recorded in a Field object. One important piece

of metadata is the finite element used to define function spaces for the field (given

some mesh). This can be defined either using the finat.ufl.FiniteElement

class, or using the same arguments as can be passed to

firedrake.functionspace.FunctionSpace (e.g., mesh, family, degree). In

this case, we use a \(\mathbb{P}2\) space so specify family=”Lagrange” and

degree=2.Since Burgers is a vector equation, we need to specify vector=True.

fields = [Field("u", family="Lagrange", degree=2, vector=True)]

The solution Functions are automatically built on the function spaces given

by the get_function_spaces() function and are accessed via the

field_functions attribute of the MeshSeq. This attribute provides a

dictionary of tuples containing the current and lagged solutions for each field.

In order to solve the PDE, we need to choose a time integration routine and solver

parameters for the underlying linear and nonlinear systems. This is achieved below by

using a function solver() whose input is the MeshSeq index. The

function should return a generator that yields the solution at each timestep, so

that Goalie can efficiently track the solution history. This is done by using the

yield statement before progressing to the next timestep.

The lagged solution is assigned the initial condition for the current subinterval

index. For the \(0^{th}\) index, this will be provided by the initial conditions,

otherwise it will be transferred from the previous mesh in the sequence.

Timestepping information associated with a given subinterval can be accessed via the

TimePartition attribute of the MeshSeq. For technical reasons, we

need to create a Function in the ‘R’ space (of real numbers) to hold

constants.:

def get_solver(mesh_seq):

def solver(index):

# Get the current and lagged solutions

u, u_ = mesh_seq.field_functions["u"]

# Define constants

R = FunctionSpace(mesh_seq[index], "R", 0)

dt = Function(R).assign(mesh_seq.time_partition.timesteps[index])

nu = Function(R).assign(0.0001)

# Setup variational problem

v = TestFunction(u.function_space())

F = (

inner((u - u_) / dt, v) * dx

+ inner(dot(u, nabla_grad(u)), v) * dx

+ nu * inner(grad(u), grad(v)) * dx

)

# Time integrate from t_start to t_end

tp = mesh_seq.time_partition

t_start, t_end = tp.subintervals[index]

dt = tp.timesteps[index]

t = t_start

while t < t_end - 1.0e-05:

solve(F == 0, u)

yield

u_.assign(u)

t += dt

return solver

Goalie also requires a function for generating an initial condition from the function space defined on the \(0^{th}\) mesh.

def get_initial_condition(mesh_seq):

fs = mesh_seq.function_spaces["u"][0]

x, y = SpatialCoordinate(mesh_seq[0])

return {"u": Function(fs).interpolate(as_vector([sin(pi * x), 0]))}

Now that we have the above functions defined, we need to define the time

discretisation used for the solver. To do this, we create a TimePartition for

the problem with two subintervals.

end_time = 0.5

dt = 1 / n

num_subintervals = 2

time_partition = TimePartition(

end_time,

num_subintervals,

dt,

fields,

num_timesteps_per_export=2,

)

Finally, we are able to construct a MeshSeq and solve Burgers equation over

the meshes in sequence. Note that the second argument can be either a list of meshes

or just a single mesh. If a single mesh is passed then this will be used for all

subintervals.

mesh_seq = MeshSeq(

time_partition,

mesh,

get_initial_condition=get_initial_condition,

get_solver=get_solver,

)

solutions = mesh_seq.solve_forward()

During the solve_forward() call, the solver that was provided

is applied on the first subinterval. The forward solution at the end

of that subinterval is transferred to the mesh associated with the

second subinterval and used as an initial condition for the same solver

applied again there. Goalie uses a conservative interpolation

operator to transfer solution data between the two meshes. In this

example, the meshes (and hence function spaces) are identical so the

projection operation will in fact be the identity.

The output is a nested dictionary of solution data, indexed by

solution type ("forward" or "forward_old") and then field name

(here "u"). The contents of the inner dictionaries are lists

containing lists of solution Functions, indexed first by

subinterval and then by timestep. That is,

solutions["forward"]["u"][i][j] contains the forward solution

associated with field "u" at the j-th timestep of

subinterval i. Similarly, solutions["forward_old"]["u"][i][j]

contains the forward solution from the timestep prior.

For the purposes of this demo, we plot the solution at each exported

timestep using the plotting driver function plot_snapshots().

fig, axes, tcs = plot_snapshots(

solutions, time_partition, "u", "forward", levels=np.linspace(0, 1, 9)

)

fig.savefig("burgers.jpg")

We see that the initial sinusoid is nonlinearly advected Eastwards.

In the next demo, we use Goalie to automatically solve the adjoint problem associated with Burgers equation.

This demo can also be accessed as a Python script.